Jinnah of the Bible

The story goes back to the Christmas of 1876 when in the home of Mithibai and Jinnahbhai Poonja was born a boy whom they named Mohammad Ali. It is pertinent to point out here that this boy was NOT floated off on a reed basket to escape an order to kill all boys... of a certain age, from a certain community. It is also pertinent to add here that this boy did NOT grow up in a foster home. But the boy had an upbringing of privilege. He grew up and learnt to speak the language of the court, the Empire’s language of logic, empiricism and substantiated debate. He was a thumping success at this. Later, he took to fighting the Empire with its own logic, its own sense of fair-play and constitutional methods.

Then one day he had an epiphany that ‘his’ people were not the people of the larger population of the land. He realised that his people instead were a smaller group, a people that at some point in the history of the land had taken up a faith of another kind. His own family had had a similar history.

After the epiphany Jinnah, as the man was increasingly referred to, decided to take his people away from being underlings of the larger population of the land to a Promised Land of milk and honey. A land so pure, so full of righteousness that the old land of inequality and injustice would become a distant dream!

Here unlike the Biblical story of Moses, Jinnah did reach Canaan... he got to see the newly-formed land of purity and righteousness. But then like Moses, he soon followed his forefathers into the great beyond leaving his people to their own devices, which ironically were in short supply. The people soon learnt that the milk and honey of rhetoric could never match up to the institutions and systems needed to administer justice and maintain peace.

With this realisation began Jinnah’s Canaan’s descent into chaos. A chaos more destructive than the one they’d been promised they were leaving behind. They realised the fact that their purity and exclusivity in fact stood on very shaky ground. Not based on the lofty ideals that they seemed to be in the beginning. Rather, they realised, that they was based on an error of perception. On defensive reasoning. On brittle egos. They realised that their Canaan was not a land of milk and honey but a sprawling necropolis, a remnant of another civilisation that was now simply called Mohenjodaro or the Mound of the Dead.

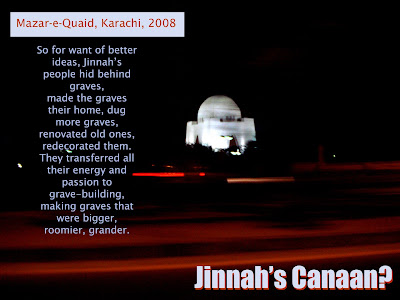

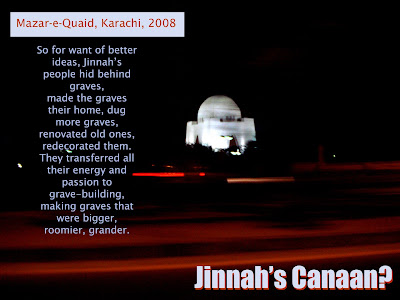

So for want of better ideas, Jinnah’s people hid behind the graves. They made the graves their home, dug more graves, renovated old ones, redecorated them. They transferred all their energy and passion to grave-building, making graves that were bigger, roomier and grander. They dedicated their scientific know-how to the pursuit of making graves. They didn’t care about food or drink, they didn’t care about their poor but built graves with a vengeance.

At some point they realised that they had more graves than people to fill them so they started training their young men to find newer, faster ways of filling up their works of passionate enterprise. They developed, not entirely on the own, a weapons system of staggering proportions, fitted with the capacity to annihilate millions at the press of a button.

So why did Jinnah’s people take on such a self-destructive trajectory?

For this we have to go back to the story in the Bible. The story of an incessant wait…

According to the Bible Moses went up to Mount Sinai to receive a Code of Living for his people and this took what looked like ages. In this time his people got restive and demanded to go back to a somewhat familiar system of being. So they collected all the gold each one had, melted it and built themselves an effigy of a calf and started worshipping it. This was the exact opposite of the form of worship Moses had in mind but that’s another story.

Jinnah, unlike Moses, never came back to his people with a Code of Living. And so they collected all their gold and built themselves an effigy of a government. An easy calf-like system that could be tweaked and bullied into looking the other way while the real work went on undisturbed. The real work was the work of making war, something Jinnah’s people were familiar with having fought their way out of the larger population of the land. The fighting took many forms, since there was no larger population to fight they began to fight each other. It was a fight for dominance. The Punjabi began to fight the Sindhi; the Sindhi, the Balochi and the Balochi, the Pathan and the Pathan, the Punjabi. And soon the Land of the Pure had not just one golden calf, but a whole dark pantheon of violence, of hatred, of funding underground wars. It had written its own Code of Killing and Dying. It had turned itself into a state, in direct opposition to the one dreamed by Jinnah. And what was worse he was not coming back. Besides there was no shortage of graves.

Today, Pakistan continues to carry on its strange and vengeful legacy, its biggest and vilest jihad against its founder. It carries on finding newer ways to negate and erase everything that he sought, everything that he argued for, going back into everything that he wanted to deliver his people from. In fact Jinnah’s Pakistan, like the Biblical story, has rubbished the very idea of a nation of based on the tenets of a faith. Was Jinnah wrong? Or what we're seeing today is a posthumous punishment... a garland of shoes that his people have taken upon themselves to put around his grave?

Then one day he had an epiphany that ‘his’ people were not the people of the larger population of the land. He realised that his people instead were a smaller group, a people that at some point in the history of the land had taken up a faith of another kind. His own family had had a similar history.

After the epiphany Jinnah, as the man was increasingly referred to, decided to take his people away from being underlings of the larger population of the land to a Promised Land of milk and honey. A land so pure, so full of righteousness that the old land of inequality and injustice would become a distant dream!

Here unlike the Biblical story of Moses, Jinnah did reach Canaan... he got to see the newly-formed land of purity and righteousness. But then like Moses, he soon followed his forefathers into the great beyond leaving his people to their own devices, which ironically were in short supply. The people soon learnt that the milk and honey of rhetoric could never match up to the institutions and systems needed to administer justice and maintain peace.

With this realisation began Jinnah’s Canaan’s descent into chaos. A chaos more destructive than the one they’d been promised they were leaving behind. They realised the fact that their purity and exclusivity in fact stood on very shaky ground. Not based on the lofty ideals that they seemed to be in the beginning. Rather, they realised, that they was based on an error of perception. On defensive reasoning. On brittle egos. They realised that their Canaan was not a land of milk and honey but a sprawling necropolis, a remnant of another civilisation that was now simply called Mohenjodaro or the Mound of the Dead.

So for want of better ideas, Jinnah’s people hid behind the graves. They made the graves their home, dug more graves, renovated old ones, redecorated them. They transferred all their energy and passion to grave-building, making graves that were bigger, roomier and grander. They dedicated their scientific know-how to the pursuit of making graves. They didn’t care about food or drink, they didn’t care about their poor but built graves with a vengeance.

At some point they realised that they had more graves than people to fill them so they started training their young men to find newer, faster ways of filling up their works of passionate enterprise. They developed, not entirely on the own, a weapons system of staggering proportions, fitted with the capacity to annihilate millions at the press of a button.

So why did Jinnah’s people take on such a self-destructive trajectory?

For this we have to go back to the story in the Bible. The story of an incessant wait…

According to the Bible Moses went up to Mount Sinai to receive a Code of Living for his people and this took what looked like ages. In this time his people got restive and demanded to go back to a somewhat familiar system of being. So they collected all the gold each one had, melted it and built themselves an effigy of a calf and started worshipping it. This was the exact opposite of the form of worship Moses had in mind but that’s another story.

Jinnah, unlike Moses, never came back to his people with a Code of Living. And so they collected all their gold and built themselves an effigy of a government. An easy calf-like system that could be tweaked and bullied into looking the other way while the real work went on undisturbed. The real work was the work of making war, something Jinnah’s people were familiar with having fought their way out of the larger population of the land. The fighting took many forms, since there was no larger population to fight they began to fight each other. It was a fight for dominance. The Punjabi began to fight the Sindhi; the Sindhi, the Balochi and the Balochi, the Pathan and the Pathan, the Punjabi. And soon the Land of the Pure had not just one golden calf, but a whole dark pantheon of violence, of hatred, of funding underground wars. It had written its own Code of Killing and Dying. It had turned itself into a state, in direct opposition to the one dreamed by Jinnah. And what was worse he was not coming back. Besides there was no shortage of graves.

Today, Pakistan continues to carry on its strange and vengeful legacy, its biggest and vilest jihad against its founder. It carries on finding newer ways to negate and erase everything that he sought, everything that he argued for, going back into everything that he wanted to deliver his people from. In fact Jinnah’s Pakistan, like the Biblical story, has rubbished the very idea of a nation of based on the tenets of a faith. Was Jinnah wrong? Or what we're seeing today is a posthumous punishment... a garland of shoes that his people have taken upon themselves to put around his grave?

Deadly.....Paksitanis may hate you for this but it's SO TRUE....a very subtle way to rubbish what Jinnah stood for!!

ReplyDeleteComparisons, i was told are odious at best. However, in this case it fits in perfectly. Its tragic that a nation that was carved out after much sorrow and violence has still not developed any distaste for both. Bible as well as Koran inisit there is a time for war and there is time for peace. Let's see when the time for peace arrives in Canan

ReplyDeleteThe broadstroak I agree with and I don't think anyone can fault that...just that it's too simplistic, viewed in hinsdsight and the light of what Pakistan has turned into now. As a student of the craft of history writing I have to say we were taught that the only fair way to look at or write about an event is to see what compelled it to happen at that time. This piece is anachronistic in that it doesn't factor in how people do ont have the ability to see to far ahead and what seems like a failed state now was inevitable, given the foces and pulls and pushes of the time.

ReplyDelete